Overview

Effective urban design requires dialogue, invention and fearlessness. Where once city planning was driven by a desire to seek out and emulate best practice, now is the time to fully unleash the potential of architects to create bold solutions to some of the major problems affecting our metropolises.

The need for more affordable housing, greater energy efficiency and a better connection between people and the environment in which they live are just a few of the pressing issues. Approaches that minimise risk are destined to keep us locked in the past; divergent thinking is necessary for our communities to evolve and progress.

The COVID-19 pandemic brought an increased appetite for rural migration as companies increasingly adopted hybrid and remote working arrangements, while some multinationals have been increasingly investing in rural infrastructure, such as Tesla’s battery Gigafactory in Nevada. Despite this, neither the necessity nor growth of cities appears to show any sign of dimming.

According to the World Bank, 56% of the world’s population still lives in cities and 80% of global GDP is generated in cities. Cities remain states’ economic barbicans and by 2050, urban populations are expected to double, meaning seven in ten people in the world will live in cities.

Urban design remains an essential tool of progress and at its heart is technology, the glue that binds together our Blended Future. Legendary Japanese architect Kenzo Tange described his profession as a union of technology and humanity. The role of technologists is more important than ever as cities’ goals become increasingly ambitious – from electrifying mobility and decarbonising buildings to creating more adaptable, multi-functional spaces that respond effectively to local and global challenges.

KEY THEMES

POLICY REINVENTION

DECISION-MAKERS MUST EMBRACE THE NOTION THAT CITY IDENTITY DOES NOT NEED TO BE FIXED.

Fundamentally, cities are highly inefficient in their current makeup because we have inherited outdated infrastructures that are too often handicapped by mobility – highways, traffic jams and pollution are familiar foes. Archaic policies are often the biggest barriers to ambition so there needs to be a shift in outlook from governments and civic leaders.

The quest for identity – either its development or preservation – is often a central focus for such decision-makers, but they must embrace the notion that identity does not need to be fixed. In the MENA region, freedom from legacy is often highlighted as a benefit, offering cities more agility and the ability to learn from others’ mistakes. But larger world cities must also ensure that they are on a journey of transformation to avoid becoming ageing relics with less dynamic economies.

TRANSFORMING SPACES

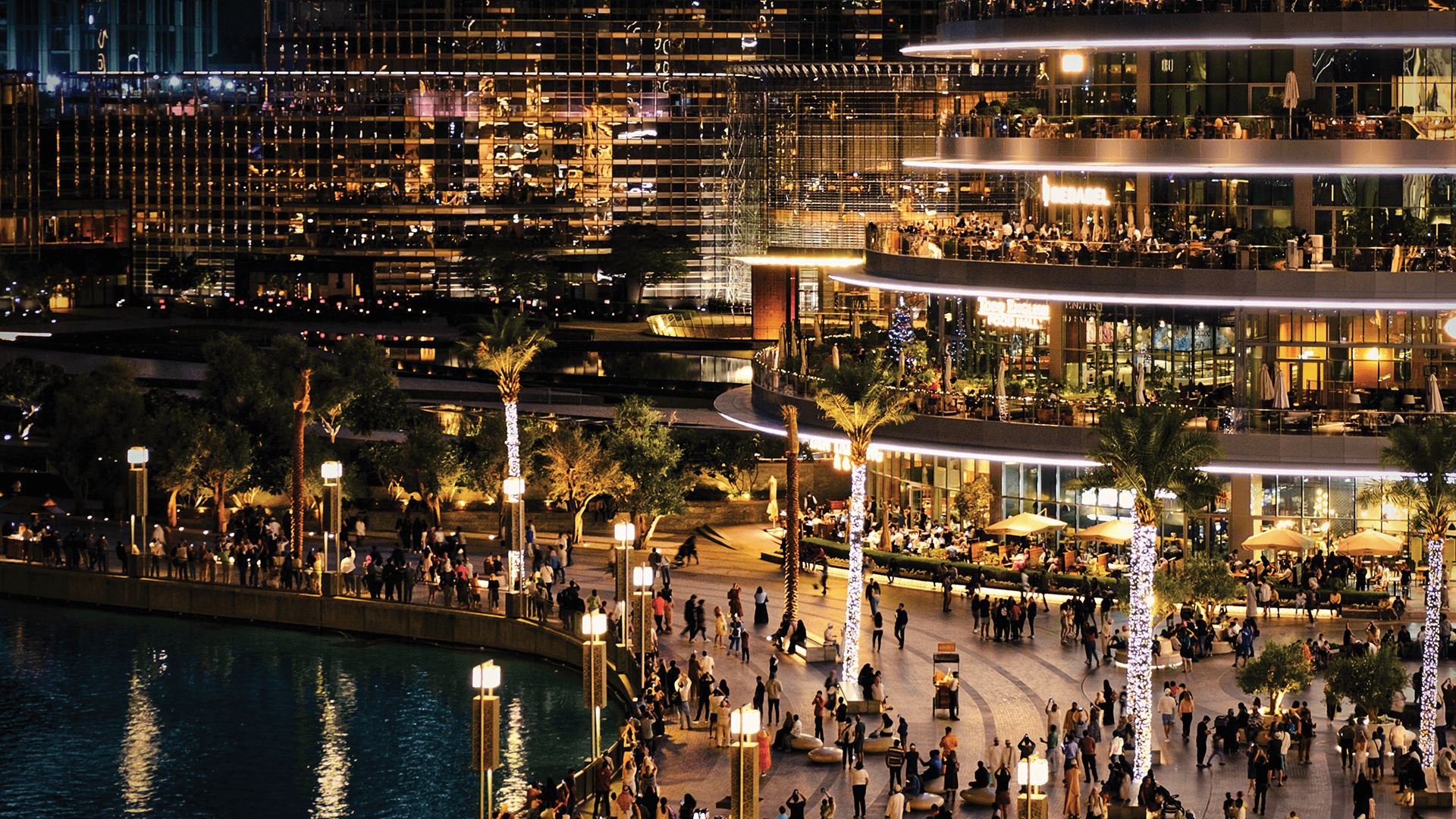

PUBLIC REALMS COULD, AND SHOULD, HAVE MULTIPLE FUNCTIONS AND MULTIPLE POTENTIAL ACTIVATIONS.

For so long, skyscrapers were seen as a city’s most aspirational assets, but in a post-pandemic world, priorities have changed. Modern urban design needs to be resilient and flexible; how well can cities cope with financial crises, extreme weather events and global pandemics?

Spaces are increasingly being designed to adapt their purpose and the one-dimensional ‘office block’ will soon be a thing of the past. These transformative public realms could, and should, have multiple functions and multiple potential activations.

Consider the many aspiring entrepreneurs to emerge in the post-COVID landscape and the spaces required to bridge the gap between pop-up and permanent premises for these micro businesses.

There is a need to maximise the utility of our buildings, whether it is transforming the top three floors of every skyscraper into a vertical warehouse for drones to be able to seamlessly deliver from place to place or ensuring that there are more green spaces readily available for those who live in high-rise residential units. Language is limiting here and perhaps it is time to develop a new lexicon. What will be our new ‘skyscraper’ and how will we label it? There are innumerable opportunities ahead.

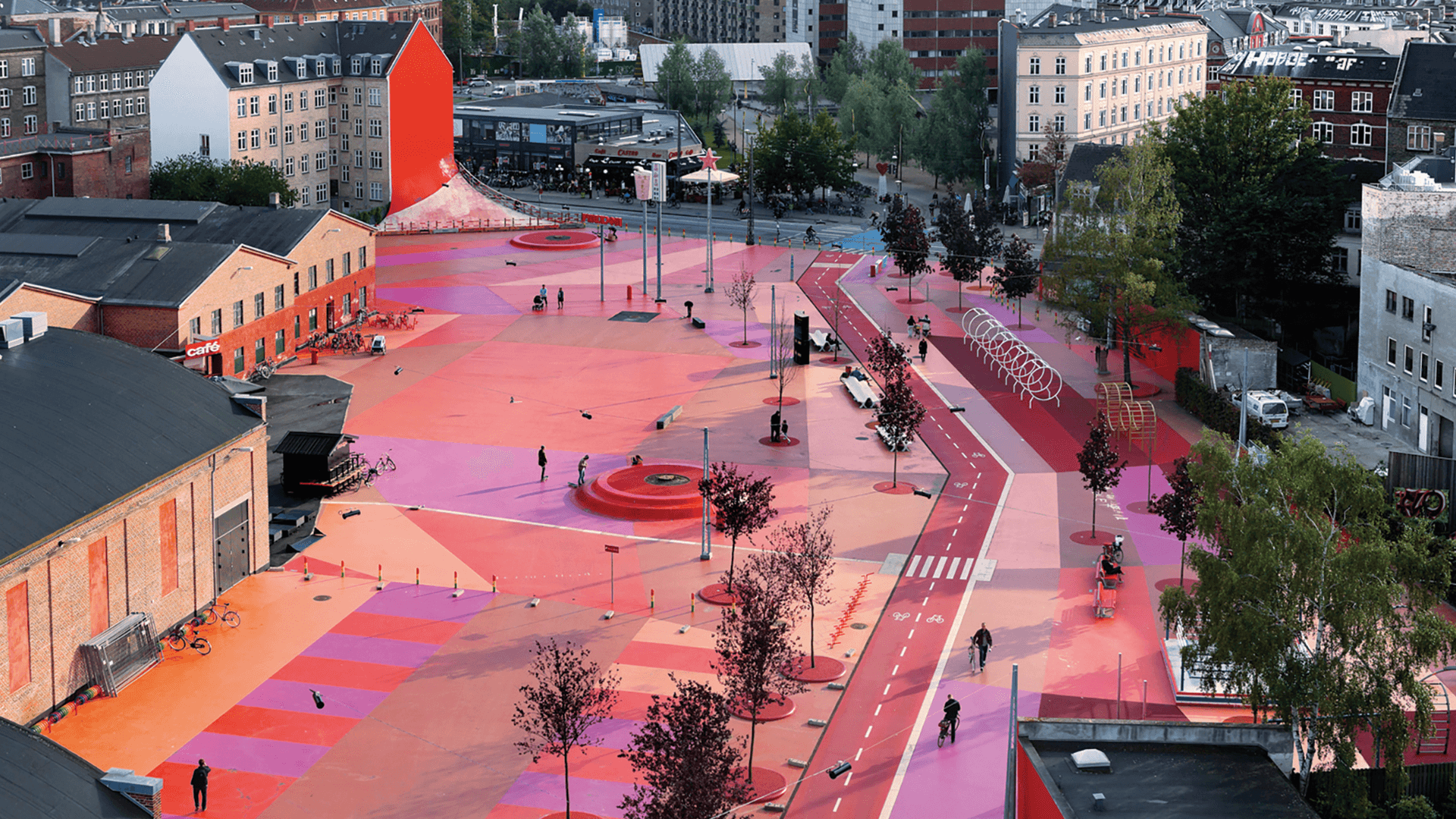

CITIZEN COLLABORATION

Research, dialogues and understanding are the central tenets of any effective urban planning. Successful architecture often borrows from archaeology; the process of digging and discovering traces of a place’s history helps shape knowledge and guide effective reinterpretation. Those who dwell in a place understand this relationship between memory and environment better than anyone else, and there is arguably no stronger influence on how cities are defined than the people who live in them.

Citizens are becoming increasingly engaged and demanding a more prominent role in the process of urban design; they want greater transparency from governments and architects, at the very least, and are ideally seeking genuine collaboration.

PROJECTS TO INSPIRE

NEOM, SAUDI ARABIA – THE LINE

Promising a ‘civilisational revolution’ that will simultaneously address the dual global crises in liveability and environment, The LINE is a 170-km-long development that will house nine million people in the new Saudi Arabian city of NEOM. The LINE is a hugely ambitious project that will run on 100% renewable energy and incorporate a sustainable transport system that foregoes roads, cars and emissions.

COPENHAGEN, DENMARK – LYNETTEHOLM

Designed in response to fears about climate-induced storms and rising sea levels, the artificial island of Lynetteholm will be both a bulwark against extreme weather for Copenhagen harbour and a 35,000-strong community set across housing and business districts. The 275-hectare project was approved after robust public dialogue – common with any large developments in Denmark – and will be built over the next 50 years.

It is the latest in a number of proposed island developments off Copenhagen which includes, most prominently, Holmene – an archipelago of nine artificial energy islands that will produce and store enough clean energy to cover the electricity needs of three million Danish households.

HELSINKI, FINLAND – HOT HEART ISLANDS

Striving to reach decarbonisation targets and with a mindset that ‘if a best practice does not yet exist, why not create it’, Helsinki is developing an archipelago of heat-storing basins that will help power the city and provide domed recreational facilities for residents.

Working with Schneider Electric, 10 giant seawater basins off the shores of Helsinki will act as thermal batteries, helping to heat Helsinki in a carbon-free way that is expected to also be 10% cheaper than the city’s current energy solutions.

MANCHESTER, UK – CASTLEFIELD SKY PARK

Taking inspiration from New York’s ‘High Line’, this 330-metre Victorian-era steel viaduct has been transformed into a freely accessible green space in the heart of Manchester.

Previously an unused relic of the city’s industrial past, the repurposing of the viaduct into the Castlefield Sky Park is expected to breathe life into the local community with its gardens, new wildlife habitats and an events space for local organisations such as the Urban Wilderness arts project and mental health charity 42nd Street.